This site is no longer being updated.

Please visit www.graemethomson.net for current news/posts

This site is no longer being updated.

Please visit www.graemethomson.net for current news/posts

Shoes off, long legs stretched out, Paul McCartney is making full use of the sofa in the elevated control room of Abbey Road’s studio two. Outside, a gaggle of tourists hang around like Apple Scruffs in training. Inside, George Martin is pottering around the canteen, the Fab Four’s likenesses hang in every corridor, and the very walls of the studio secrete historical significance. It’s all vaguely oppressive. “Yeah,” grins McCartney, glancing around. “Get out of that, man!”

It’s late summer 2005 and McCartney has just completed Chaos And Creation In The Back Yard, a two-hander with Radiohead producer Nigel Godrich. The experience appears to have left him somewhat tenderised. Having bumped into Godrich earlier, I can see why. As McCartney’s PR man raved about his 1980 album track “Temporary Secretary”, Godrich interrupted to briskly dismiss the song as “dreadful, awful.”

McCartney, it transpires, has had a bit of a rough ride on his thirteenth solo album. “I’d bring songs in and Nigel would say, ‘No, I don’t like that. It’s a bit ordinary, can you think of a new tune for it?’ ‘Whaaaat?!!’ One day he said something about a song we’d been doing. I’m not sure if he said, ‘I think it’s crap,’ but it sounded like that to me, and we had a bit of a plunge into the darkness. I ended up saying, ‘Look, I think I’ll knock it on the head for today.’

“We came in the next day and talked. He said, ‘Oh, I didn’t think you’d take it like that.’ I said, ‘Come on man. What do you think I am? I’m like you. If you knock my confidence then it’s knocked.’ If you’ve been around long enough and done well and had hits, you put on a face, a front. It’s not necessarily the truth.”

As the afternoon wears on, McCartney is persuaded to contemplate the twists and turns of a deceptively varied post-Beatles career. “I don’t really see a thread running through it,” he says. “I was just trying to make a path away from the Beatles. We were all feeling a bit, ‘Oh, fucking Beatles.’ Some of the very early stuff now sounds sort of hippy, a little bit ‘Glastonbury’. McCartney was a home-baked pie. I was plugged into the back of a Studer four-track, so it’s very, very raw. It was great fun, very therapeutic and quite a brave, nutty thing to do, I suppose. Ram was echoing my lifestyle, going to Scotland with a new family and being very free. It was good to break out in other directions that I hadn’t necessarily experimented with. It seemed like too soft an option to just do Beatles songs and get a big super band around me.”

When he finally formed a band, McCartney experimented with democracy. “Coming out of The Beatles, I’d got burned by being told I was too overbearing, so I really backed off too far in the early days of Wings. Having to be diplomatic and say ‘Um, perhaps we should do this?’ doesn’t work. Eventually somebody says: ‘Why don’t you tell us what you want?’ and I’d think, ‘I just got a bollocking for doing that!’ There was a bit of that in early Wings which caused difficulties.”

It’s been a recurring theme, the difficulty in finding collaborators who won’t wilt in the shadow of the McCartney legacy. After all, how can any writing partner follow John Lennon? “Well, he was certainly the best. Just a bit! We came through our evolution together, so we knew what each other was thinking.”

I always got the sense your creative dialogue lasted as long as Lennon was alive.

“Yes, I was very aware of that. I remember reading that when John heard ‘Coming Up’ he said, ‘Oh, bastard McCartney. I’ve gotta write again!’ It reminded him of the standards we both could reach. It’s interesting that it was a little song like that, not particularly earth-shattering. It would happen to me too. I’d hear something and go, ‘Oh, here we go again.’ It was a great thing, like a see-saw.

“Elvis [Costello] was good fun to work with. Very forthright! We would sit around for a few hours with acoustic guitars and scribble something down, kind of like John and I had done. It was cool, because we could go downstairs into the studio and immediately make raw demos – some of which are better than the finished records. They’re hot off the stove and really pretty cool. But I’ve certainly had other collaborations when I’ve thought, ‘This is just not working,’ just because it wasn’t that interesting.” I ask for names. He smiles a refusal. “I don’t want to say who, because it would be a put down on the person. It’s like telling out of school.”

With that, he stretches, slips on his shoes, ruffles his suspiciously dark hair, and lopes off downstairs for some “veggie nosh”. Later, slightly lost in the labyrinth of Abbey Road, I bump into him again. “Alright, Graeme?” he asks, “Can I help? I’ve been here a couple of times, I think I know the way…”

I was very sad to hear of the death of Mark Hollis on Monday, February 25, 2019.

The music he made with Talk Talk, and the solo album he released in 1998, is some of the most beautiful and mysterious I have ever heard. There wasn’t much of it, but it touched me deeply for 30 years. For anyone who hasn’t heard The Colour Of Spring, Spirit Of Eden and Laughing Stock in particular, I would urge immediate investigation.

I spent most of the Monday night and Tuesday morning following his death writing a piece for the Guardian on the beauty of Hollis’s voice and words. Several other writers also contributed pieces. Orchestrated by Laura Snapes, the Guardian‘s coverage in the aftermath of his death was superlative. The various pieces are collected here, and they are all excellent.

In the years before Hollis’s death, I wrote several other pieces about Talk Talk. Here are some of them:

Talk Talk: 10 of the Best – the Guardian, May 2017

Talk Talk: Natural Order review – Uncut, January 2013

The Band Which Disappeared From View – the Guardian, September 2012

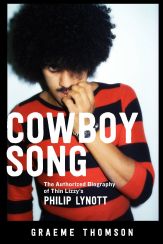

A tremendously positive 10 / 10 review of Cowboy Song has appeared on PopMatters:

‘It is … difficult not to acknowledge that Cowboy Song might be one of the best rock biographies of all time.’

Read the full review here.

The latest coverage of Cowboy Song in the US includes reviews by Under the Radar, Austin Chronicle, and a feature in Houston Press.

The latest coverage of Cowboy Song in the US includes reviews by Under the Radar, Austin Chronicle, and a feature in Houston Press.

I was also pleased to get commendations from Craig Finn and Cass McCombs, two writers and musicians I admire greatly:

“Cowboy Song is pretty amazing. I’ve been a Lizzy fan for a long time but I learned a massive amount of new things from the book and it made me love them even more.” – Craig Finn, The Hold Steady

“I’ve always held it impossible for biography to encompass a life, especially the life of someone as vibrant as Phil Lynott. Cowboy Song has changed my mind. A touching portrait of one of my favorite musicians.” – Cass McCombs

Out now, published by Es Pop Ediciones, in rather fine style.

Cowboy Song is published in the US this week, by Chicago Review Press. It is available at all the usual outlets, including Amazon and Barnes & Noble.

I recently wrote a blog for CRP on my favourite Lynott songs.

Behind The Locked Door was published in paperback in the US at the end of 2016. Here are recent reviews from the Houston Press and from Rockyoulike

Lewis Merenstein, who has died, produced Van Morrison’s Astral Weeks, and executive-produced the follow-up, Moondance. I interviewed an obviously frail Merenstein last year. Here is the full transcript of that conversation, about the making of Astral Weeks – and Afterwards.

‘Van’s manager Bob Schwaid and I were friends, and he got me involved. I went to Boston at Bob’s request to hear Van. We went to ACE recording studio, I walked in and he was sitting on a stool. He played me “Astral Weeks” and it took me about 30 seconds to know I wanted to work with the material: “If I venture in the slipstream…” He was being born again, he was going through the tunnel and coming out again. The lyric went straight to my soul, or my spirit. To me it was very clear what he was saying, but nobody else knew what the hell he was talking about, because it wasn’t “Brown Eyed Girl”.

I came from a jazz background, and I heard jazz chords that could be played with it. After 15 minutes I went to Bob and said, “Let’s go do it!” We took Van and went back to New York. Bob and I were sharing a space off of Sixth Avenue, we had an office in the front and a little rehearsal room in the back, and it seems like Van unpacked, came over and we started doing it. It was definitely something that was being guided by a greater power. At that time Van was very passive. He was coming from Bang Records and Bert Berns, and they were pretty aggressive people, and he was coming from a hit song, and choruses, and I felt something was going on. Something was being born. I know he was not conscious of the full dimension of it.

I came from a jazz background, and I heard jazz chords that could be played with it. After 15 minutes I went to Bob and said, “Let’s go do it!” We took Van and went back to New York. Bob and I were sharing a space off of Sixth Avenue, we had an office in the front and a little rehearsal room in the back, and it seems like Van unpacked, came over and we started doing it. It was definitely something that was being guided by a greater power. At that time Van was very passive. He was coming from Bang Records and Bert Berns, and they were pretty aggressive people, and he was coming from a hit song, and choruses, and I felt something was going on. Something was being born. I know he was not conscious of the full dimension of it.

He needed a place to stay, and he needed a new deal. We’d sit around the office and he’d play tunes, and I’d mark on a piece of paper the songs I thought would go together for this album, and which ones would be for the next album. He had most of the material for Moondance, but I sensed a story in these songs. I’d never heard any of those tunes before. I selected a story which I thought was going on in Van’s internal life at that time. He would just keep playing tunes. Van wasn’t much of a conversationalist, and I never said, “What did you mean by this?” I knew what he meant. What little I learned about him on our trip back to New York, I knew what was happening.

It came through you. It was magic. It’s hard to give the feeling a voice. It was beyond amazing.

He had some players from Boston, a flute player and a bass player, but they were young and not terribly accomplished, and they weren’t of the calibre I was used to using. I knew I needed people who could pick up the feeling. I had used Richard Davis quite often, and he was a highly renowned bass player. He was special. Richard made a call to his regular buddies. Connie Kay was with the Modern Jazz Quartet, and Jay Berliner was a fine, fine guitarist of any nature. They were all just marvellous players, super pros, and they were open souls. They played right from the heart.

Warner’s had a small rehearsal studio, and we went in there to rehearse. Larry Fallon wanted to come and hear what was happening and see if he could contribute. Right away he wanted to do this and that, and I said, “Larry, it’s not that kind of an album. It has to come out the way Van is expressing himself. After that is done we can see what touches might be needed. I don’t want any charts, I want the direction to come from the music.” I didn’t want it to turn into a rock and roll album.

I told Bob I was going to book a studio – we might as well do what we’re going to do. It was a union date, there was nothing sacred about it. We went into Brooks Arthur studio [Century Sound]. I told the players what I meant, and Van went into the booth. It wasn’t even a closed booth, it was one of those tall fibreglass booths, so you could look out. I said, “Go.”

If you listen to the very first tune, “Astral Weeks” Richard leads, and he leads all the way through. He lays the groundwork. It was magical, musically magical. It was so beautiful, it was hard to take. There were no charts. They might have run the first few minutes of a song down a couple of times, and then we did it. There was never a full take. There was nothing more to be said, there was nowhere to go. It was all there. Everybody got the sense of what was being said musically, even if they didn’t get what was being sung verbally by Van. It was like a musical puzzle that fit perfectly.

He interacted very little with the other musicians. He had a habit of turning his back on people. He was very nervous, he was like a little child – he was truly being born again. He had [his wife] Janet Planet. I don’t know what transpired between being with the Bang people and then coming to Boston, but he obviously went through a rebirth. It was like a story, like a little play. If Van knew that it was deep down in some place that was never conveyed.

I sat and listened to that album almost every night for a year, because I had no one to talk to about it

With “Slim Slow Slider”, there was nothing left to put on that album. We needed time. It was the mood of an ending, I was following the sensitivity of the music and using my own sense of creativity. Nothing else could end the album. I don’t know what was taken out of that song. Nothing terribly memorable. If you hear the reverb at the end of it, it’s tape reverb, and when we had enough time I stopped it. I’ve always wished I could make up a story that would satisfy someone who wanted an observation of what was going on. All I know is that whatever happened, happened. Everybody was in it. Richard was bent over his bass with his eyes closed, listening to Van.

I was totally blown away. It came through you. It was magic. It’s hard to give the feeling a voice. It was beyond amazing.

We overdubbed strings in another studio, Masterphone, and the horns were done in the same studio. Larry went in with them. They weren’t full string sections, they were small, and they didn’t play too much. On “Astral Weeks” they come up and across, cascading up and down the other side. It wasn’t very intricate, but it was fulfilling. We did horns on “Young Lovers Do”. I wasn’t particularly happy with that. Van was there, he had comments during the string overdub. Once he felt safe enough to be verbal, he was verbal. It was mostly mumble or grumble. He was given the gift as we all were. He’s a marvellous talent, but at times I don’t believe he knows what’s going on. He was the most removed from it. He didn’t look for answers, he just did it. I knew I had been given a gift, and an opportunity. I don’t think Van had a clue how special it was, it was just part of what he was writing.

I put on the label, In The Beginning and Afterwards. He screamed, “Who told you to do that?” I said, “No one, I just felt it. That’s my two cents worth.”

I sat and listened to that album almost every night for a year, because I had no one to talk to about it besides Bob. Joe Smith at WB said, “What the blank did you give me?” “What did you expect Joe?” “Something like ‘Brown Eyed Girl.’”

We couldn’t get him booked. People wouldn’t stop eating and drinking when he was playing. Rolling Stone made the album. After close to a year, no one would mention it, and then [RS reviewer] Ben Fong Torres was respected, and everybody all of a sudden discovered it and started playing it. That was the miracle of it.

We couldn’t get him booked. People wouldn’t stop eating and drinking when he was playing. Rolling Stone made the album. After close to a year, no one would mention it, and then [RS reviewer] Ben Fong Torres was respected, and everybody all of a sudden discovered it and started playing it. That was the miracle of it.

The album was like an ending. From there he was flying away, and out of that came a happier person, which was Moondance.

Moondance was sad for me. He could be pretty wild back then, he was drinking. Van started pulling away from Bob, [manager] Mary Martin snatched him from Bob. Everything suddenly became Van, Van, Van, Van. I don’t know how many producers he went thought at WB.

It was a more pragmatic album. That’s what he learned up in Woodstock, so that I could be killed off. It was put together at the WB rehearsal studio. I picked the songs out, up at the WB studio, I did the road map for that album when we were rehearsing, and then I got demoted. I heard he had thrown a bass across the studio, and for me that was it. It became a nasty situation. Mary talked Van into getting rid of everybody, he wasn’t going to come up with another album unless I gave myself another title and Bob was out of it totally. I chose to go along with it. I made sure WB got the tapes, got the union papers. I think he was angry that he couldn’t claim Astral Weeks. But I’m terribly proud of the album, and I’m so glad I heard what I heard when I heard it.’